Hi everyone. I’ve learned that if I get 5 more reviews on Amazon for The Book of Dog by Lark Benobi then I’ll be eligible for some promotional programs. If you’ve written a review on GR and not on Amazon, it would be a tremendous favor to me if you would also post on Amazon. Thank you and sorry for the wee promotional intrusion. Here is a picture of some whiptail lizards. .

.

Month: September 2018

There is a lot I don’t love about Amazon but I am stunned & happy to see that they automatically linked the three versions of The Book of Dog on their site, without me asking–and also, THANKS to everyone who has left a review of The Book of Dog on Amazon, too!

I’m so grateful to Ilana Lucas for including The Book of Dog by Lark Benobi in her review of “3 New Books About Unusual Woman Warriors,” published in the online magazine Brit + Co today. I especially liked this part:

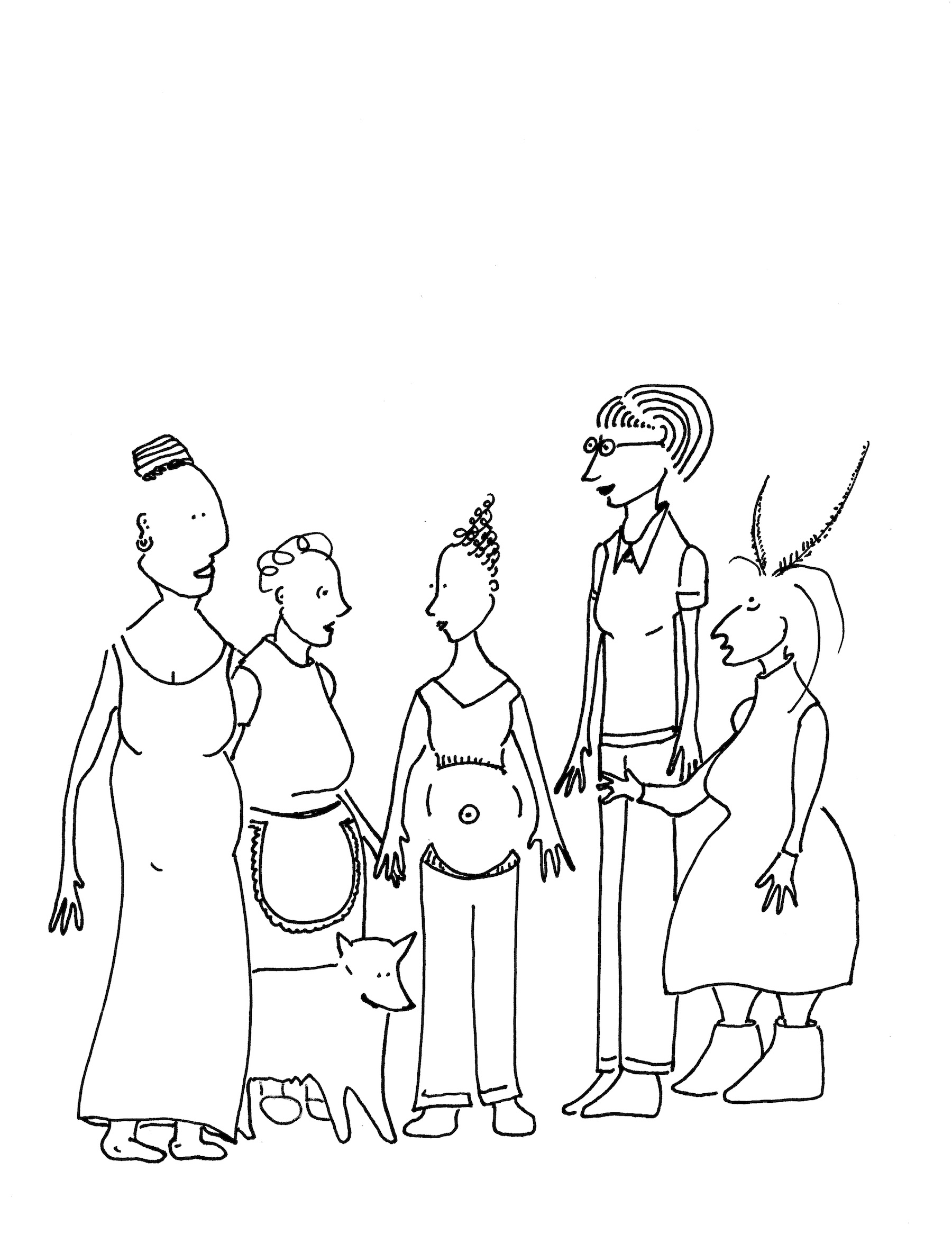

“The book serves as a metaphor for female powerlessness in male and religion-dominated societies, but its six heroines are still willing to kick ass and take names…the irreverent and fantastical novel is filled with evocative, stylized cartoons and is an ode to friendship. Individually, they may not be able to change very much, but together, every dog has her day.”

Here is a link to the full review.

I feel really good when readers describe my book as an “ode to friendship,” in particular, as an ode to female friendship. The novel was inspired and shaped by my friendships with other women, especially the friendships I have made since November 2016, with women I’ve met at marches and readings and gatherings of like-minded crones… we women are just now beginning to find our collective political power.

As I write this I’m listening to Bob Woodward, Superhero, talking with Terry Gross about the most dangerous man who has ever sat in the White House. It seems likely I will be reading FEAR by Bob Woodward very soon, along with about a million other people.

But so many other readings–not all of them new–have helped me cope and helped me to understand the world, since Trump’s election. Here are a few off the top of my head. I’ll probably post some more later. Deepest apologies for these all being men, this time–I will make it up one day.

- Frederick Douglass: “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro” (July 5, 1852) Douglass’s white friends seemed to think there was nothing untoward about asking a man who had suffered slavery to give the Independence Day address to the Ladies of Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester New York, and a time when nearly four million people were enslaved in the United States. What they got from Douglass was a masterpiece of rhetorical oratory and the most eloquent definition of white privilege ever written, even though the term ‘white privilege’ wasn’t current in the 19th century. After setting the 600 people at ease with his patriotic introduction praising the Founding Fathers, he confronts them with their hypocrisy, and asks: “why have you invited me to speak to you on your Fourth of July?…The Fourth of July is yours and not mine…You may rejoice, but I must mourn.” Profoundly moving. Douglass’s speech reminds me that we have been here before, and what is true and right is the same today as it was in Douglass’s time.

- Runagate, Runagate: a poem by Robert Hayden. Hayden’s subject is the flight of enslaved African Americans to the north; with only slight changes it could just as well be about the flight of Latino refugees to the north. I like to be reminded that terrible things have been overcome before in this country.

- Signs Preceding the End of the World by Yuri Herrera. A border story, about a very young woman making her way confidently and fearlessly through a world of men, many of whom wish to do her harm, and yet the young woman prevails, she triumphs, she finds a way to be fully alive and fully happy even with danger all around her. Much of what I love about Signs Preceding the End of the World has to do with what is not explained. The human relationships and even the landscape itself keep changing, shifting, in mirage-like realignments of feeling and color. The truth is never laid out in explicit detail and it seems right for the novel to remain in many ways unknowable, just as so many things that might happen on a journey across the border can’t ever be fully understood, or fully in control of those who make the journey. This novel gave me the sense of the border as an organic living country in its own right, with dignity as well as degradation, and hope as well as despair.

- The Plot Agains America by Philip Roth. Ignore anything you have been told about Roth’s treatment of his female characters long enough to read this book. It is one of those rare books that, like 1984, seems to capture our age before it happens. Granted, I am a Roth fan, but believe me, the women here are the core of the story and they are beautiful and deeply imagined characters.

- The Sarah Book by Scott McClanahan. I’ve already recommended this novel, here, when I said the novel taught me more about despair in West Virginia than reading sixteen billion profiles on Trump voters ever could. The people in McClanahan’s book seem real. Maybe they are. They are unique individuals who are coping with the stress of living in an impoverished state, where jobs are few, and hope is just a cynical memory of a feeling, and where becoming an addict seems like a reasonable life choice, and where living in a Wal-Mart parking lot is just the way things are. Read it to expand your empathy in an unexpected direction, perhaps.

well, five seems enough, for now.

On Sept 17 I’ll be speaking on a panel with some marvelous writers at Bookshop Santa Cruz and if you are within hailing distance it would be wonderful to see you there.

At the bottom of this post is a link to the event, and also, here is the essay that originally inspired me to organize the event (and to write The Book of Dog!) : “Writing in the Age of Trump,” originally published on the inspirational and super-smart website, “Women Writers, Women’s Books.”

And because this is me being intellectual, rather than completely silly, here is this serious selfie of me listening to the smashingly fine climax of the opera Don Giovanni while standing in front of Rodin’s Gates of Hell…which is exactly right for my book, as you will know, once you have read it.

~ lark benobi

Writing in the Age of Trump

I want to tell you something surprising. I want to tell you how Donald Trump has changed my writing forever, and in wonderful, empowering ways. I will begin my story on the night of November 6 2016, just after the state of Pennsylvania had tipped for Trump. In that moment I experienced an overwhelming need to write down how it felt to witness Mr. Grab-em-Etcetera become Leader of the Free World. I wrote very fast. I stayed up all night. I was so angry. I had no idea that millions of women on election night felt the same way until we all showed up on January 18 the following year for The Women’s March, the largest worldwide demonstration in history.

What I wrote that night didn’t turn out to sound so angry when I looked at it the next morning. Instead it made me laugh. And this was the first sign of the motivating magical power of Donald Trump, Muse. What I wrote on election night in a fit of anger eventually became the fourth chapter of a new novel, The Book of Dog, a political satire that early reviewers are calling “uproarious,” “laugh out loud funny,” and “raucous fun.” How did it happen? It beats me.

Something about that shock of that night propelled me toward the healing force of humor, even though I had never written humor before.

As the novel began to take shape–very quickly, it turned out–I thought a lot about the many ways that, In unsettled political times, good satire can upend typical ways of thinking. I was excited to be writing some. You would think satire would be thriving just now. But it turns out that Trump’s election upended satire completely.

If you search online for “Satire in the Age of Trump” you will discover a trove of articles that contend that satire is now on life support. Comic impersonation and exaggeration and shock humor are the tools of modern satire, but they are the wrong tools when the President can out-shock the best of us. What good are insult-driven jabs, when Trump is the master of them? What good are jokes that demean and mock, when we elected a Mocker in Chief?

So satire would need to change. In the age of Trump, satire would need to become less reptilian and more mammalian. It would need to become warm-blooded and swift, instead of stomping around like Godzilla. In an age when bad people are empowered by ugly talk, satire could not talk ugly in turn. It would need to get kind. With each draft of The Book of Dog I tried to be as kind as possible, both to my characters and to my readers. I tried to take tender care of everyone.

I’m not talking about censoring the message, by the way. It’s amazing the satirical lengths one can go to when speaking politely. Trump’s election had changed the map of what was funny, and what was not. I needed to use better diction. I needed to leave the salty Anglo-Saxon curse words for another time. I needed to write my outrage in the most elegant way possible. I needed to whisper it. I needed to re-read Voltaire. Did you know that Voltaire wrote a scene in Candide much like the scene in The Road by Cormac McCarthy? The one where humans are being stored as living meat to be consumed one piece at a time?

McCarthy made his scene revolting, and Voltaire made the same scene hilarious. After reading Voltaire’s scene I realized anything is acceptable, if you say it sweetly enough. And then I watched Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictatorand rediscovered how satire can do more than make you laugh, or feel superior. It can elevate and encourage. It can leave you hopeful instead of angry. Watch The Great Dictator and see for yourself, especially this scene.

Here’s the thing: it’s not only satire that has been upended by the Age of Trump. I honestly believe that language, and the way we use language as writers, has been fundamentally disrupted by the election of a man who has such an easy relationship with the truth. Something big and unmapped is happening to all kinds of writing these days–to language itself, both the way it is used to communicate, and the way it is used to dissemble. You may have discovered your writing has changed in response, no matter what your chosen genre.

Walt Whitman wrote: “these are the days that must happen to you.” These are the days that compelled me to write a humorous farce about six women who face an Apocalyptic Beast, a.k.a. “The President.”

These are the days that must happen to you, too, and to us all, as women and as writers: days when what is ‘fact’ or ‘fake’ changes with the flip of a digital dial; when #metoo truths are called “lies” by powerful men; when simple and innocent messages on a twitter feed can become tomorrow’s viral outrage. Language itself is under attack. Words seem less reasonable and predictable than ever before.

As women writers we will need to be crafty. We will need to write bravely, and at times into uncomfortable new territories. We will need to listen to one another. We will need to support one another. These are the days when more women than ever before are finding their voices. I thank Donald Trump for it. What happens next might surprise us all.

—

Lark Benobi began writing The Book of Dog on election night 2016, and drew inspiration for her story from the women who are speaking out, running for office, marching, and doing all they can to improve our world. Lark lives in Santa Cruz, California.

About THE BOOK OF DOG

It’s the night of the Yellow Puff-Ball Mushroom Cloud and a mysterious yellow fog is making its way across America, sowing chaos in its path. Mt. Fuji has erupted. The Euphrates has run dry. The White House is under attack by giant bears, the President is missing, and the Vice President has turned into a Bichon Frise. It’s Apocalypse Time, my friends. Soon the Beast will rise. And six unlikely women will make the perilous journey to the Pit of Nethelem, where they will stop the Beast from fulfilling his evil purpose, or die trying.

It’s the night of the Yellow Puff-Ball Mushroom Cloud and a mysterious yellow fog is making its way across America, sowing chaos in its path. Mt. Fuji has erupted. The Euphrates has run dry. The White House is under attack by giant bears, the President is missing, and the Vice President has turned into a Bichon Frise. It’s Apocalypse Time, my friends. Soon the Beast will rise. And six unlikely women will make the perilous journey to the Pit of Nethelem, where they will stop the Beast from fulfilling his evil purpose, or die trying.

The Book of Dog is a novel of startling originality: a tale of politics, religion, demon possession, motherhood, love, betrayal, and easygoing bestiality. A ridiculously plausible story set in a near-future America, it wryly explores how even the most insignificant and powerless of people, when working together, can change the world.

LINK TO BOOKSHOP Santa Cruz EVENT:

Do you wake up every day as I do, to a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when clouds hang oppressively low in the heavens, and a crushing despair is strangling your soul, because your country is being led by an amoral, self-interested, ignorant, and possibly demented old man with his finger on the nuclear button?

Ok, true, the best solution for this feeling for each one of us to vote in the mid-terms, and volunteer at a phone bank or two, and do everything you can to avert this Apocalypse by voting them out in November.

But also, you could use some REALLY GOOD ESCAPIST LITERATURE just about now.

So here you go–my recommended required reading for times exactly like this one.

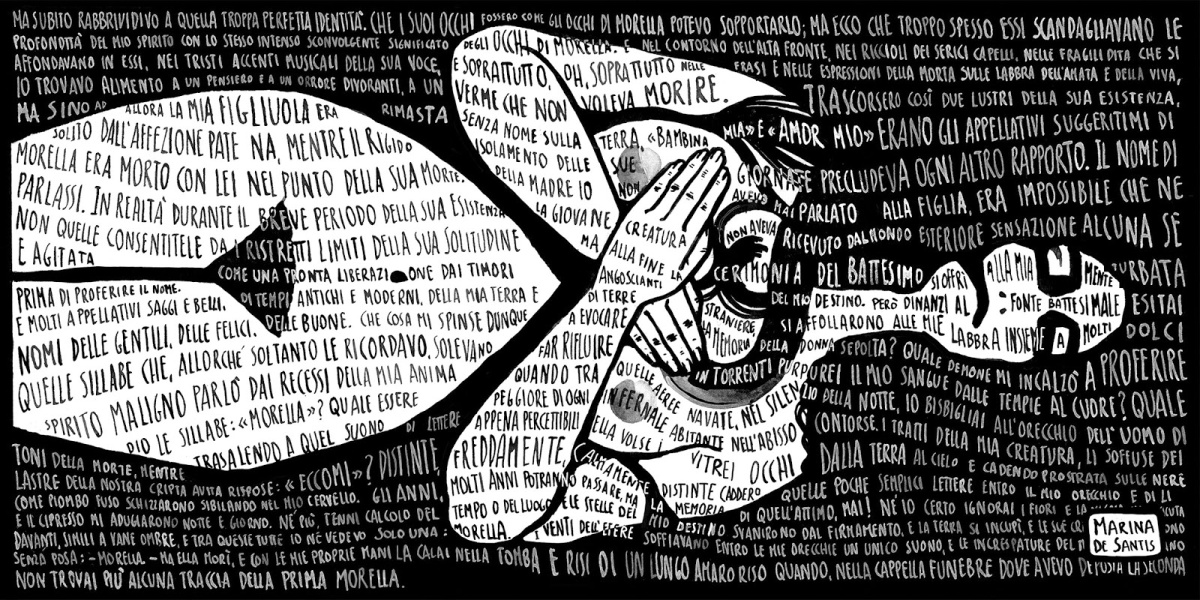

FIRST: READ ANYTHING BY POE. You probably haven’t thought of him for decades. Start with the lovely love story, Berenice, and then move on to the weirdest novel ever written, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. You will be so confused that you will momentarily forget your despair.

SECOND: Read PYM by Mat Johnson, which achieves the astounding outcome of making Poe’s novel funny. Best if read immediately following The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. Pay attention to the dog backstory for best results.

THIRD: Read LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF JOAQUIN MURIETA: CELEBRATED CALIFORNIA BANDIT .

Novelist Tommy Orange mentions this novel in his 2018 novel, There There, in a somewhat disparaging way. Too bad. OMG, this is the best escapist novel I have ever read. Published in 1854, it is probably the first novel written and published by a Native American author, John Rollins Ridge. It’s breathless and remarkable and pulpy and escapist but also it’s old enough to have become of interest to literary scholars who plumb its deeper meanings. Like in this essay, published in The Paris Review.

FINALLY, read Rootabaga Stories by Carl Sandburg.

I could have also put The Wind in the Willows or The Wizard of Oz, both of which are so beautifully written that they should be required escapist re-reads every year of your life, but I picked this one thinking you may have missed reading it somehow as a kid, and you owe it to yourself to read these stories at least once. They are very strange. They don’t unfold the way they should. And in this way they will preoccupy you and dazzle you and make you forget there is any such thing as a bilious yellow-orange character charading as president just now.

-Lark Benobi, author of, and fan of escapist literature

Most authors want their readers to feel safe enough to turn the next page.

But for some authors, ‘safe’ just won’t do. There are a few brave authors who write books where you will feel more assaulted than nurtured. Books where the view of humanity is bleak, and where the characters don’t care what you think of them.

It’s amazing how often I end up really hating this kind of book and everything about it, only to turn around days or sometimes years later and realize I have never stopped thinking about them. Reading these books was a transformative experience. They changed my mind and my heart. There are probably gentler ways to wrest readers out of their complacent ways of thinking but just now it feels like authors must make a choice–they must either support a reader’s current ways of thinking, or the must risk losing readers in order to shake them out of their complacency.

Here are some books that shook me. I recommend them all. But maybe not all at once.

ALMANAC FOR THE DEAD by Leslie Marmon Silko

This novel is exorbitantly, lavishly violent. It’s a sordid kind of violence, violence done to and by characters with a pathological level of cruelty. It was impossible to not feel assaulted by it as I read. It jolts me right out of my complacency about the past. This is a novel about Native American genocide, about American genocide. It’s about a holocaust that has been more or less lost to history in terms of its overwhelming magnitude, and where what is remembered has been kitsched over and transformed into popular entertainment. Silko set out to shatter the past as it has been preserved in our collective culture and to replace it with something far more damning and sad.

Much of the writing is staccato, scattered, shattered, and at times nearly incoherent. Silko tells a story of lives brutalized. It’s a story where proper sentences would prettify and thus lie. The stylistic punches built up a level of dread in me as I read. There are scenes of such brutality and lack of humanity that they left me sick. I also frequently felt lost, and irritated by a prose style that felt deliberately blunted and ugly. ANd then I would think: this is right, this is the right way to tell such an ugly history.

Now and then would come chapters of soaring lyricism, interstitially spaced between the chapters of violence and cruelty. They fortified me. They allowed me to keep reading.

It’s maybe my highest praise of a book when I can honestly say “I’ve never read anything like this book before.” And I admire how ruthless Silko is, even though there are passages I wish I could un-read.

CULT-X by Fujinori Nakamura

This is a story where human agency is helpless before the crushing weight of history and propaganda. The entire notion of free will is revealed as a sham. I was repulsed by the ugliness of this novel, and by the sexual violence, and by the passivity of the female characters, and by the hopelessness of the story itself. Some scenes read like infantile sadistic male fantasies. I kept trying to frame these scenes in a literary light. I kept trying to believe these scenes had literary value beyond their face value. I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t find a scrap of redemptive value in them.

And then I read John Nathan’s review of The Rise and Fall of Modern Japanese Literature by John Whittier Treat, published in the August 16 2018 New York Review of Books. Even though Nathan never mentions Cult-X, Nathan does mention other popular Japanese novels, some of which are still to be translated, and all of which seem as disturbing as Cult-X, or even more so. Nathan’s essay reminded me that Japanese writers are working from inside the horror of their recent history: the madness of unquestioned nationalism, the razing of whole cities by firebombs, the horror of two nuclear attacks, the death tolls from earthquake and tsunami; and then add to these the way any hope for the future has been crushed by the crash of a bubble economy, the rapid aging of the population, and an economy that continues to stagnate and to offer little opportunity for the next generation. Reminded of these things, I discovered that my first reaction to this novel, to reject its nihilism, began to feel like a privileged person’s naive understandings. I could see this novel anew. It’s still not a fun read, but it is a thought-provoking one.

Goat Mountain by David Vann

Goat Mountain by David Vann is the second most ruthless book I’ve ever read. Number 1 in the most-ruthless category is Dirt by David Vann. Numbers 3,4, and 5 on my ruthless books list would also be novels by David Vann.

There is no other author who is so skilled at combining poetry with viscera. The combination is Homeric. It commands your attention. Vann’s novels remind you that life-and-death stories are actually, literally about life and death. Each of Vann’s novels invokes the heightened tension of the best genre thriller, but goes so far beyond that genre-level dread, because the stakes in these books are real, and they are enormous. Vann books make me gasp with their audacity. In my head as I read Vann’s books I hear these questions: Is he really going to write that? And: Did he really write that? and with each of his novels I feel the same wrenching understanding, as I read, that I’m going to be brought to a level of primal violence, a level that I hadn’t been able to imagine being inscribed in language before then.

Goat Mountain is my favorite of Vann’s books because the story is so fundamental and pure. There is absolutely nothing extraneous in its pages. It’s like the last few seconds of a Greek play, in novel form. It’s Oedipus gouging his eyes out. It’s Agamemnon cutting his own daughter’s throat.

It does not surprise me at all that Vann’s latest book, Bright Air Black, is a retelling of the Medea myth. It is a lovely visceral rendition that you should also read, both for its fierce feminism and for the unbeatable scene of Medea scraping her brother’s putrid remains off the deck of Jason’s ship with a wooden spoon.

And it also does not surprise me that in the acknowledgments of Bright Air Black Vann writes “my novels are all Greek tragedies.”

For me it is in Goat Mountain where Vann’s love of Greek tragedy is displayed at its primal and perfect best.