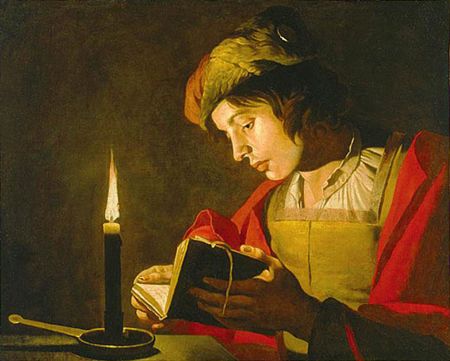

Just lately I’ve tried reading novels the way I might visit an art exhibit. When I visit an art exhibit I have no need to make steady progress. I expect to look at a thing from all angles, up close and far away. I spend more time in front of things that draw me in. I might go back again before I leave, just to experience them one more time. And when I go home, for a while at least, it feels as if everything–the sidewalk, the cars and buses, my own hand–is something I am seeing in a new way.

In contrast I typically read a novel as if I’m on a steady hike. No lingering or backtracking allowed: getting to the end in the most efficient way possible was my implicit goal. If I don’t like where the novel appears to be going I get impatient. I’m constantly looking for reasons to put a book down when there are so many others to be read.

I started to wonder if I’d enjoy reading more if I allowed myself the freedom to read books the way I look at art: without a destination in mind, and without judgment.

I decided to try it.

The first novel I read this way was Frontier by Can Xue. It turned out to be a lucky choice because the novel is anything but linear. I could open Frontier at a random page and it felt like just as reasonable a place to start as any other. I read Frontier in random chunks, a paragraph or two at a time, and I also read it the other way, from left to right and beginning to end, and it took me weeks before I felt ready to leave it, and it didn’t matter to me how long it took, because something contemplative and delightful happened to me as I read and I didn’t want it to be over.

When I was done the novel made sense to me beautifully, especially if I thought of it as a Rothko painting, because at first the novel seemed to have just one color to it, but the longer I stared at it, the more I saw how many colors there really were.

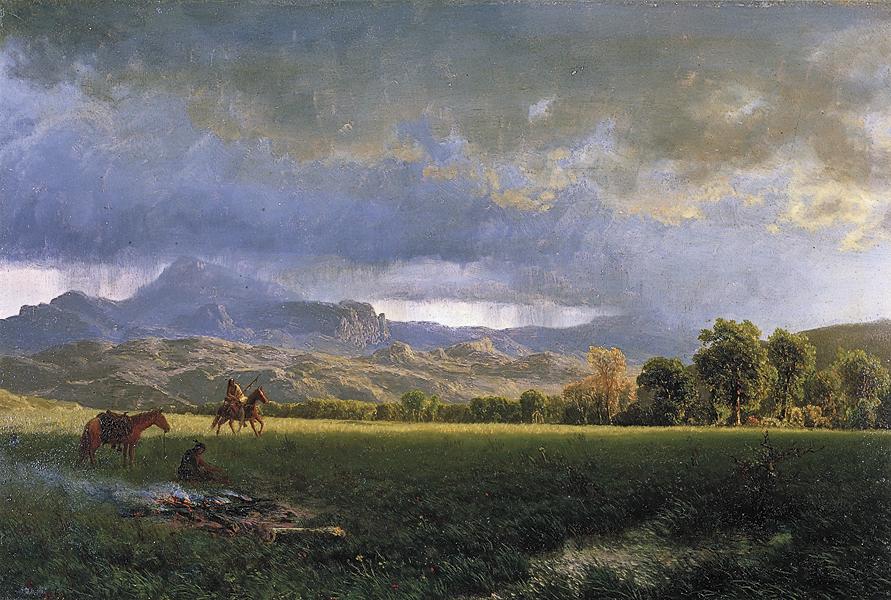

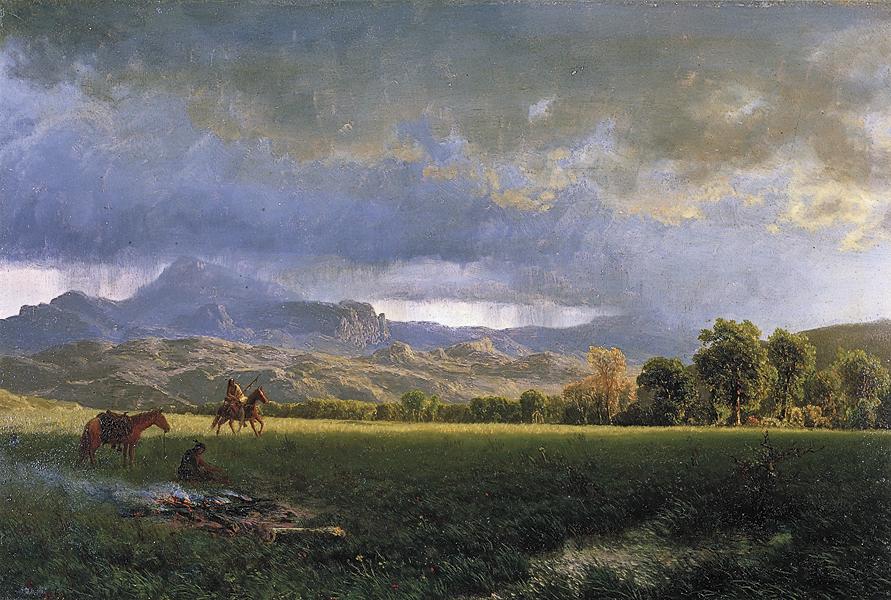

Later I read In the Distance by Hernan Diaz. I resisted everything about it in the beginning. I though this novel was impossible to believe in. And then I gave up trying to make the book conform to my old way of reading, when I was full of purpose and expectation.

I tried instead to read the novel as if I were looking at an unexpected painting on a wall, artist unknown. In such a situation, I would offer the artist more courtesy, and more patience. And the next thing I knew as I read Hernan Diaz’s novel I was inside a scene of such great beauty–even though it was about a man cutting his beloved burro open in a futile attempt to save its life–that I thought, for a while at least, that this book was the best thing I had ever read. Art will do that to you.

I began to read every novel with the meandering curiosity of a stroll through a gallery, rather than with the critical efficient purposefulness I had usually read. I tried doubling back as I read, just as I might double back to see a favorite painting in a gallery. Sometimes I read a chapter over completely, either because I liked it, or because it confused me. I gave myself permission to look harder, and to spend more time in one place, rather than trudging gamely toward the end. Or to start over entirely.

I read Radiant Terminus by Antoine Volodine this way and I discovered the book had a Jackson Pollock-like, patterned randomness.

I re-read Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko, and decided that reading it was something like looking at…

…a Joan Miró,

…and after that I read Fever Dream by Samantha Shweblin, a book that once might have annoyed me with its unfinished vague edges…

…until I thought of it as an Andrew Wyeth painting, one of those ones with broken fence posts in the snow.

To read a book this way is more than a metaphor to me now. I realize now that I had thought of myself as a literate person, and all the while I had been reading in the same stolid way I had been taught in first grade, from beginning to end, and at a steady pace. I had never revisited the usefulness of that way of reading a book. Now I was reading differently. I liked it. What I’m trying to describe here is a deep attention. A willingness to be open to the unexpected. A willingness to forge your own path through a book, and to take your time, and to withhold judgment of both the book and yourself. To listen and forgive. To learn to read anew. Go see some art. Then, read a book.

– Lark Benobi

(buy The Book of Dog by Lark Benobi)