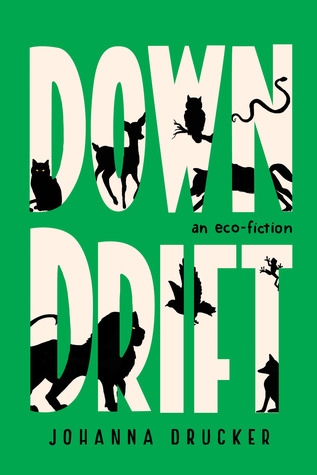

Downdrift by Johanna Drucker is a book that amazed and delighted me, even though as a cohesive narrative it fails completely. Fail is the wrong word, though, for a goal that is never attempted. This novel doesn’t want to be judged for its storytelling, and it is not so much a novel as it is a sometimes-whimsical, sometimes-serious thought collage.

As the novel begins, organisms in every ecological niche on Earth have begun to experience the intrusion of human-like characteristics into their behaviors. This change is presented as the opposite of evolutionary progress: to behave in a human way is instead categorized as “downdrift.”

The story is narrated throughout by “Archaeon,” a unicellular organism that belongs to the Kingdom Archaea, a creature that has (through contact with others of its kind) absolute knowledge of events the whole world over, but that has almost no sense of narrative suspense.

Archeaon explains its sense of narrative timing this way:

Our time scales–yours and mine–are as different as our size and complexity. To me, all of the follies of the animal kingdom are the trivial business of a few seconds of my historical memory. Nearly three-quarters of the earth’s existence has passed in my presence, billions of years. Compare that to the mere millions in which primitive arthropods and other organisms came into being. And you? A blip on the screen, a tweak in the evolutionary chain, a phenomenon of rapid acceleration. I will long outlive you and the changes wrought on this world by your machinations.

What forward narrative momentum there is in Downdrift (and it barely registered with me as I read along) hangs on the stories of a lost cat and a peripatetic lion, creatures that re-appear at intervals in the story, and that seem destined to meet at some point. And they do meet. But that meeting seems beside the point when it happens, because the real delight of Downdrift is not in narrative at all, but in an accumulation of detail, sentence after sentence, that by the end paints a picture of vast ecological disruption.

Another round of salamander antics is taking place in the autumn woods. A big group outing, comprised of extended families and pseudo-families, is underway at the edges of a pool. They have collected food bright as their red bellies or the stark yellow of their spots. The older ones are picking at a few, very few, highly colored bits of fungus and mixing them with all manner of beetles and flies, worms and larvae, spiders and moths and grasshoppers to make a banquet from an ancient recipe. These traditions may also soon be at risk, but not yet.

In a brave choice on the author’s part Homo sapiens barely signifies in this novel at all. At one point coyotes are stealing human babies; at another point Archaeon wryly observes “an outbreak of human shoaling, seepage into the homo sapiens from the minnows and sardines,” an image that carries with it both the idea of humans under stress, as well as the lack of significance that humans and their problems have to this story.

Because this is not the human’s story. The subtitle to Downdrift is “an eco-fiction,” and the novel fulfills the goals of this relatively new genre in a significant way. The novel is a metaphor for the way we value convenience over preservation; the way we prioritize the artificial over the natural; the way we focus on our daily worries rather than the long-term problem of potential ecological collapse. For those who have the willingness to let the a story flow past at its own pace, the novel offers a unique and thought-provoking take on the world and our place in it.

– Lark Benobi